Do friendships at the workplace make you more successful?

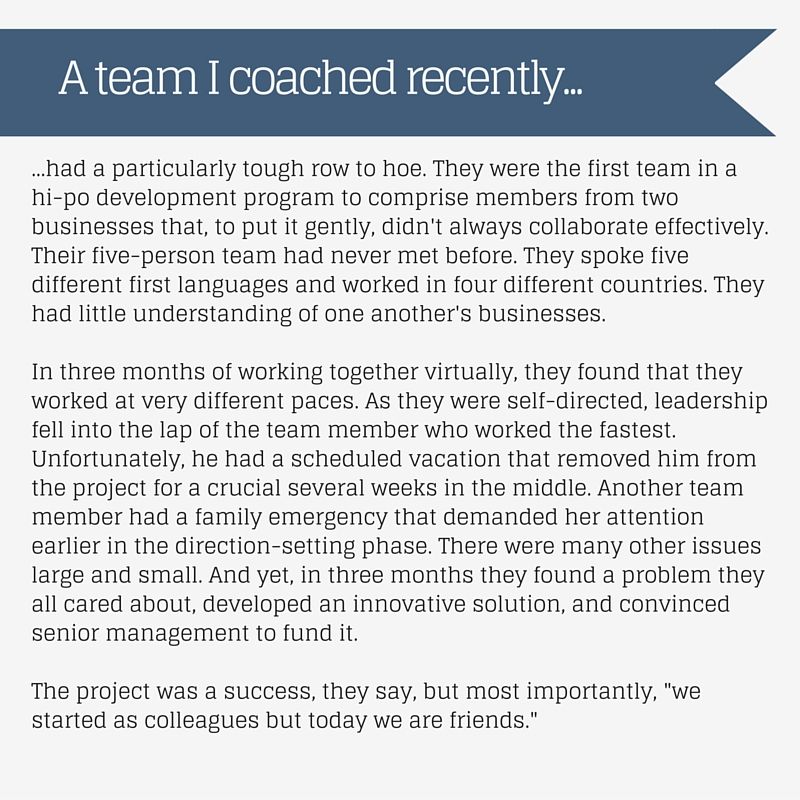

In our business of accelerating team performance, my colleagues and I have observed virtually every permutation of friends and strangers tackling team projects. This outcome is very familiar: teams of strangers who face a challenge together make the best of their individual strengths, and pull success from the jaws of defeat. Then they realize they have become friends and call that the most important outcome. It’s like every Marvel movie ever made.

More important to their employers, they stay in touch, willingly help one another professionally and often personally, and develop new ideas together.

When we put teams together for our three-month programs, we don’t have the ability to put friends together on teams, so we focus on creating the opportunity for people to become friends.

Adam Grant wrote recently about how people, Americans in particular, are less likely to make friends at work now than they used to be. Now, according to Grant, “work is a more transactional place. We go to the office to be efficient, not to form bonds.” *

Grant writes: “When friends work together, they’re more trusting and committed to one another’s success. That means they share more information and spend more time helping – and as long as they don’t hold back on constructive criticism out of politeness, they make better choices and get more done.”

Teams that lack that trust never perform up to their potential. I have seen teams start with tremendous ideas but then direct their attention to who was, or was not, pulling their weight. They become “performance police” rather than focusing on the success of the project and the team. I have seen teams get distracted by who was getting more face time with senior executives or who would benefit most from the outcome of the project.

Much has been written about the need for trust on teams and strategies for building that trust. They all take time. Shared experience makes friends and experience takes time.

What’s more, organizations can realize performance benefits just from the process of becoming friends.

Making new friends is hard. It’s risky, it leaves you vulnerable, there’s not usually a clear moment when you cross the line from colleagues to friends and you might not both do it at the same time. So in that becoming friends time, the uncertainty makes you more attentive to the other person’s cues. Attending to those cues not only helps you become friends, it helps you work better together.

But people can work together for a long time without becoming friends. So how can an organization facilitate friendships?

Here are four aspects of a work experience that will set the stage for friendships to form. Think about them next time you create an assignment.

- Duration: Short team building exercises and social events don’t work because it takes time to make friends. A long term deliverable of, say, a few months, and the prospect of future work together makes a huge difference in whether people will invest the time to get to know one another.

- Divergence from the familiar: When people step out of their comfort zones, friendships are more easily made. Think about how much easier it is to make friends with someone on a train in a foreign country than on the subway headed to work. Divergence from typical work responsibilities is important also as it removes concern about encroachment on turf or someone having a disproportionate advantage or responsibility.

- Intensity of the experience: Easy, mundane experiences are not going to facilitate friendships. Success in the face of adversity is better.

- Latitude/self direction: The more free you are to choose how, when and where you approach a task, the more you reveal your preferences you’re your style and the more your colleagues get to know you.

Yes, people are less likely to make friends at work when it’s easier to maintain contact with existing friends and outside interests, but they still will – given the right circumstances. The advantages to peoples’ satisfaction, effort, and productivity are worth it. It’s worth creating situations in which people make friends.

* It’s possible that we always went to the office to be efficient and that what’s changed is the cultural requirement to pretend that coworkers are friends. Grant writes, “We took our families to company picnics and invited our friends for dinner.” Was that because we were friends or because there was a cultural expectation that we did? If coworkers were more likely to be friends then were they more productive? I’m not sure the data would support that.