When Do We Think?

Here’s an interesting juxtaposition of data that suggests why we’re not as creative as we’d like to be.

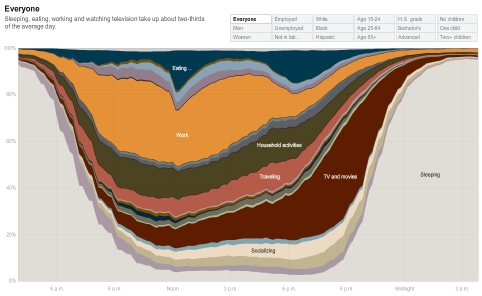

The New York Times published a fantastic infographic, How Different Groups Spend Their Day, that can keep a data junkie like me entertained for hours. The chart shows the results from the American Time Use Survey that asks thousands of Americans how they spend every minute of their day.

You can break down the data to view only certain types of people, e.g., specific age groups or states of employment or family size. You can also view specific activities, e.g, sleeping, eating, working. As I played with the data I was struck by one particularly thin line, Relaxing and Thinking, which is described as “doing nothing” or “sitting around.” The data shows that we as a country spend about 16 minutes a day relaxing and thinking. Not surprisingly, employed people spend less, 11 minutes per day. People with advanced degrees spend the least as a group at 8 minutes and people age 15-24 are also at the low end of the range at 10 minutes.

Consider that data in light of recent research described in the Wall Street Journal: A Wandering Mind Heads Straight Toward Insight, which finds that

In fact, our brain may be most actively engaged when our mind is wandering and we’ve actually lost track of our thoughts, a new brain-scanning study suggests. “Solving a problem with insight is fundamentally different from solving a problem analytically,” Dr. Kounios says. “There really are different brain mechanisms involved.”

By most measures, we spend about a third of our time daydreaming, yet our brain is unusually active during these seemingly idle moments. Left to its own devices, our brain activates several areas associated with complex problem solving, which researchers had previously assumed were dormant during daydreams. Moreover, it appears to be the only time these areas work in unison.

“People assumed that when your mind wandered it was empty,” says cognitive neuroscientist Kalina Christoff at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, who reported the findings last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. As measured by brain activity, however, “mind wandering is a much more active state than we ever imagined, much more active than during reasoning with a complex problem.”

So creativity and insight happen when our mind is “wandering” yet we allow ourselves precious little time for doing nothing. Ten minutes a day or a third of our time, which is it? I don’t know many adults who spend a third of their time daydreaming. My eight-year-old daughter, on the other hand, would definitely bring the average up but children under 15 aren’t included in the survey data.

How much more creativity and innovation would happen if we just left ourselves more time to think? Much has been written recently about the detrimental effects of working too hard and the benefits of time to do nothing. And while there may be some forward-thinking companies promoting sabbaticals and more flexible hours, they are fighting an uphill battle to change habits and social norms that are cultivated from childhood. Unfortunately, we seem to be moving in the opposite direction with even worse consequences than losing our creative edge.